The Linux export command is built into the bash shell and has one main purpose – marking Linux environment variables that should be passed to child processes. Critically, it does so without affecting other environments.

Why is this needed? Well, every time you open a new shell session, Limux environment variables are set. If you need to change any of these variables during your session, then the shell itself has no way to select the change. This is where the Linux export command comes in – you can update the current session with changes you have made to the child process.

What are environment variables in Linux?

In Linux, an environment variable is a named, stored value that is used to determine how a shell and its processes behave. They are used to modify how certain aspects of a Linux system work; for example, the LANG variable can be used to change the language the system displays while the PATH defines which directories the system should look for executables in. Admins can also define their own variables.

How to list Linux environment variables

How the Linux export command ties into perhaps best explained by some examples:

How to list Linux environment variables

To check what environments are already set to you can use the printenv command. Here is an example of the output on an Ubuntu host:

You can also list specific variables by writing their name after the printenv command:

SHELL=/bin/bash

PWD=/root

LOGNAME=root

XDG_SESSION_TYPE=tty

MOTD_SHOWN=pam

HOME=/root

LANG=C.UTF-8

SSH_CONNECTION=213.112.50.62 52862 206.166.251.243 22

LESSCLOSE=/usr/bin/lesspipe %s %s

XDG_SESSION_CLASS=user

TERM=xterm-256color

LESSOPEN=| /usr/bin/lesspipe %s

USER=root

SHLVL=1

XDG_SESSION_ID=1

XDG_RUNTIME_DIR=/run/user/0

SSH_CLIENT=213.112.50.62 52862 22

XDG_DATA_DIRS=/usr/local/share:/usr/share:/var/lib/snapd/desktop

PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/usr/games:/usr/local/games:/snap/bin

DBUS_SESSION_BUS_ADDRESS=unix:path=/run/user/0/bus

SSH_TTY=/dev/pts/0

_=/usr/bin/printenvprintenv HOMEOutput:

/root

How to change Linux environment variables with the export command

How exactly this process works is best explained by some examples:

Example 1: Changing LANG with the Linux export command

One example of a Linux environment variable is LANG in Ubuntu, which determines the language in which programs will communicate.

One way to find your current LANG value is by executing the export command using the -p option, like so:

export -p LANG

Bash will output a list of all exported variables on your system and their values, including LANG. This is useful if you don't know exactly what variable name you're looking for. Here's a snippet:

declare -x DBUS_SESSION_BUS_ADDRESS="unix:path=/run/user/0/bus"

declare -x HOME="/root"

declare -x LANG="C.UTF-8"

declare -x LESSCLOSE="/usr/bin/lesspipe %s %s"

declare -x LESSOPEN="| /usr/bin/lesspipe %s"

declare -x LOGNAME="root"

declare -x USER="root"

declare -x XDG_DATA_DIRS="/usr/local/share:/usr/share:/var/lib/snapd/desktop"

declare -x XDG_RUNTIME_DIR="/run/user/0"

declare -x XDG_SESSION_CLASS="user"

declare -x XDG_SESSION_ID="1"

declare -x XDG_SESSION_TYPE="tty"

An easier way to query find the current value of LANG, however, is to run echo $LANG. This will output your current language, which in our case is C.UTF-8.

Now let's install the German locale and use the Linux export command to change the LANG variable to it:

locale-gen de_DE.utf8

export LANG=de_DE.utf8

If we run echo $LANG again, we'll see that its value is now LANG=de_DE.utf8. Type vi test and you'll see that the language is now German.

Example 2: Exporting your own variable

You can export your own bash variables as well as modifying already exported ones. Let's first create a variable:

yourvar=3

If we type echo $yourvar, you'll see that it returns an output of three.

But what if we move to a different shell instance, for example, by switching user? echo $yourvar doesn't return an output.

Now let's switch back to the original shell and make it an environment variable with the Linux export command:

export yourvar=3

Now it is available as an environment variable to all subshells, users, and shell scripts in the session:

echo $yourvar

3

su otheruser

echo $yourvar

3

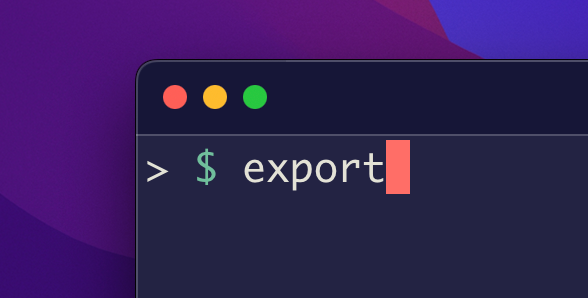

Example 3: Adding something to the path

This is potentially the most common use of the export command. Adding something to the path lets your system easily find the command or executable file. For example, you can add a bash script saved in the /bin directory:

export PATH=~/bin/script.sh:$PATH

Now when you type script.sh anywhere, it will run the script – in our case, by printing "Hello World!".

Making your changes permanent

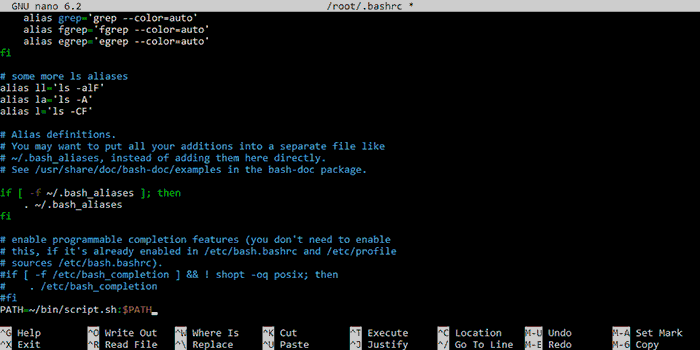

If you want your changes to be maintained after you exit the session, you need to save them to your ~/.bashrc file.

To do so, edit .bashrc with sudo nano ~/.bashrc or sudo vim ~/.bashrc and add the text you typed after your export command to the bottom of the file. For example: